QueerStory

The Story of "ALBERT"

The Story of “ALBERT”

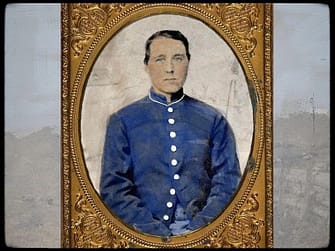

Albert Cashier was a transgendered pioneer from the nineteenth century, who’s best known for valiantly fighting for the North in the Civil War.

Albert was born in Clogherhead, Ireland in 1843, and became a stowaway to America at a young age. Working in shoe factories and as a farmhand, Albert presented as a boy in the years leading up to the Civil War, so as to live and work independently. He first enlisted in 1862 and was assigned to the 95th Illinois Infantry, where he fought for three battle-hard years until being honorably discharged in 1865. Upon returning to Illinois, he had all intentions of living his life as the quiet man his fellow soldiers knew him to be. He succeeded for the most part, working odd jobs here and there as a janitor, cemetery worker, and street lamplighter. Even when a few people in his life discovered his sex due to illness or injury, he was so beloved that they never disclosed it to anyone else.

It wasn’t until he started showing signs of dementia in 1913, and was placed in a State Hospital, that his sex assigned at birth was discovered and he was forced to wear women’s clothing again - after 50 years of living life as his true self. Once the Veterans Pension Board discovered this, they threatened to cancel his pension because, in their minds, he had committed fraud. However, the men from the 95th regiment appealed to the board, arguing that Albert was the person they fought side by side with in the war, and that his payments should continue for life. When Albert died on October 10, 1915, the men from his regiment ensured he was buried in his uniform, and with full military honors. They also made sure his tombstone was inscribed "Albert D. J. Cashier, Co. G, 95 Ill. Inf."

Swords & Roses

Swords & Roses

Hortense Mancini was known as a writer, a socialite, the richest woman in Europe - and the most promiscuous.

Born in Rome in 1646, Hortense was whisked away to Paris by her mother in the hopes of finding an opportune marriage for her. She was proposed to by the then exiled Charles II of England, but Hortense’s family forbade the match on the grounds that it was a match with little promise of advancement. This decision proved a horrible mistake when Charles was reinstated as King of England. This brief affair was not the last time Hortense and the King became “intertwined.”

Hortense survived an abusive marriage, a number of relocations (and a few affairs to go along with them), only to eventually land in London. She had some notoriety in English society by then, having become one of the first women (along with her sister, Marie Mancini) to publish her own memoir. It was then where she became reacquainted with King Charles II, taking the place of the Duchess of Portsmouth as the king’s mistress.

Lady Anne Fitzroy, the illegitimate daughter of King Charles II, just so happened to be living in the palace at the same time as Hortense. Born in 1661, Anne Palmer lived as the unrecognized daughter of the king until 1672, when he then bestowed her the surname of Fitzroy. She was married at the young age of 13, and was living in the palace with her husband and father when Hortense arrived. After Anne became pregnant at 15, the two women found deep friendship with each other, Hortense spending many evenings in Anne’s bedchambers. Rumors began to fly, and even though both Anne’s husband and mother demanded she stop spending time with Hortense, the king defended his daughter. This gave both ladies the courage to become a little more public with their affair, even sparking some mention in one the first “gossip rags” The Gazette. This publicity concerned the king, and he ordered Anne’s husband to take her away from the palace to his seat at Herstmonceux Castle in Sussex. It is reported that Anne could do nothing but lie in bed and cry for her lover.

Hortense fell from the king’s favor, but the two remained friends until his death. She remained well provided for, even becoming the rumored lover of the playwright Aphra Behn, and notoriously hosting and presiding over some of the best salons in London for a time.

One Little Thing

From the beginning, William “Billy” Haines had lived a life that was unusually open for a gay man born on January 2, 1900, in Staunton, Virginia.

He was 14 when he ran away with someone he referred to as his “boyfriend.” The two wound up in Hopewell, VA, where they worked in a DuPont plant by day and ran a dance hall (that may also have been a brothel) by night. By 1919, Billy had ended up in New York and had found success as a model. Modeling brought him to the attention of talent scout Bijou Fernandez, who got him on a train to Hollywood as one of Goldwyn Pictures’ New Faces of 1922.

By 1930, Billy was the number one male star at the box office, he’d been living with his boyfriend, Jimmy Shields, for five years and was best buddies with Joan Crawford. While he hadn’t made any announcements about his sexuality, Billy had made no efforts to hide it, either. But things were changing. Over the next few years, the studios became increasingly concerned with their image and the newly introduced Production Code was pressuring them to create films that reinforced traditional values – and to make sure their stars’ lives did the same. Soon enough, Billy was told to do one little thing: marry a woman and send Jimmy packing. Otherwise, he could kiss his fabulous life goodbye.

Billy chose Jimmy and turned his back on Hollywood – as an actor. With the help of Joan Crawford, he parlayed his well-known skill at interior design to become the decorator to the stars – in Los Angeles and beyond.

When Billy died in 1973, he and Jimmy had been together for 47 years. Joan Crawford called them “the happiest married couple in Hollywood.”

New Universe

Nicolaus Copernicus is famous for publishing his heliocentric model of the solar system, that is, that the earth revolves around the sun and not the other way around.

In 1543 Europe, this was both revolutionary and heretical. But few know about his one and only pupil, Georg Joachim Rheticus. Rheticus was born in present day Austria in 1514 and, by the age of 22, was appointed professor of arithmetic and astronomy at the University of Wittenberg. Rheticus was, over the course of his life, a mathematician, astronomer, cartographer, navigational-instrument maker, medical practitioner, and teacher. He was also someone who believed in the ceaseless search for the truth and living in that truth. It comes as no surprise, then, that Rheticus refused to marry and got into a fair amount of trouble with his less than discreet love affairs with stable boys.

Upon hearing about Compernicus’ theory, Rheticus took a leave of absence from the University of Wittenberg to visit Copernicus, uninvited, and convince him to publish. Over the next four years, Rheticus split his time between his teaching duties in Germany and visiting Copernicus in Poland, driving Copernicus to publish his theory. When Copernicus finally agreed to publish, Rheticus was not mentioned in the book’s dedication, nor given any credit for his work.

Rehticus was eventually driven from Wittenberg and then Leipzig for his dalliances with the local young men. He died at the age of 60 in present day Slovakia, all but forgotten for his contributions to Copernicus’ work. But Rheticus had several students of his own and spent the entirety of his life searching for Truth and bringing it to light, no matter how revolutionary it may seem.

Enter the Fool

Pamela “Pixie” Coleman Smith was an illustrator, writer, and publisher who is most known for illustrating the Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot deck. First published in 1909, it is still the mostly widely used tarot deck.

Born in London in 1878, Pixie spent her early life in Manchester, Jamaica, and Brooklyn before settling again in London at the age of 21 after the death of both her parents. As she established herself as an illustrator and writer, she was often exoticized for her childhood spent in Jamaica and was seen as having an air of mysticism, something that attracted famous occultists like W.B. Yeats and Bram Stoker.

It is through these connections that Pixie was commissioned to illustrate Arthur Edward Waite’s tarot deck. Waite was no artist himself and gave detailed instructions of what he wanted each card to depict. Even still, chances are that a lot of the artwork was Pixie’s invention and interpretation. When the deck was first published, it was called the Rider-Waite tarot deck, called so because of A.E. Waite and the Rider publishing company. It was years before Pixie’s contributions to the deck were recognized.

Soon after the Rider-Waite deck’s 1909 publication, Pixie withdrew from her famous occult friends, converted to Catholicism, and lived another forty years with her “companion” Nora Lake.

The Queen's English

In the early half of the 20th century, queer Londoners created and used an anti-language called Polari.

This was a way to discuss in public things that may have caused them to end up in prison: the trade they’d picked up the night before, the ridiculous outfit their friend thought they could pull off, what they thought of the handsome waiter. It also became a way for queer folk to identify each other - dropping a little Polari in one’s conversation was an easy way to find out who else might be, as polari-speakers would say, bold. Polari was derived from a unique combination of dialects used by theatre workers, traveling carnival workers and performers, sailors, and Romani travelers, with influences from Romani, Yiddish, and Cockney rhyming slang and backwards slang. Many of these influences can be seen in a common Polari greeting: “How bona to vada your dolly old eek” (How nice to see your dear old face).

Polari went widely unnoticed or understood by the general population well into the ‘60s. With the cultural revolutions of the ‘60s, queer culture became seen as edgy and fashionable and queer folk were empowered to be more outspoken. Polari began to work its way into standard vernacular British and gained popularity from media producers and writers as a way to sneak risque jokes past the censors. One of the most prominent examples of this is the BBC radio show “Round the Horne,” a comedy variety show that aired from 1965-1968. One of the recurring sketches was “Julian and Sandy” about two gay friends who spent each episode working at a new business that catered to a specific clientele.

Polari fell out of use in the late ‘60s for two main reasons. First, with it becoming popular and understood by the general public thanks to shows like “Julian and Sandy,” it lost its power as an anti-language. It hardly seems worth using a coded language if everyone knows the code. Second, the Sexual Offenses Act of 1967 decriminalized homosexual acts between two conscenting men. The need to use coded language began to fade when discussing what someone did with that handsome waiter the night before wouldn’t land them in prison. While there are few left today who are native speakers, Polari has had an impact on British English. Words like ‘naff’ and ‘frock,’ used very commonly in British English, came from Polari.

The Thwarted Love of Annemarie Schwarzenbach

The life of Annemarie Schwarzenbach was an adventurous one, a passionate one, and sadly, a short one.

From the time she was born in Switzerland in 1908, Annemarie led an educated life. Her mother started dressing her in boy’s clothing from an early age, which gave Annemarie an androgynous look that would fascinate both men and women for the rest of her life.

After graduating from the University of Zurich with her doctorate in history at just 23 years old, Annemarie made her way to Berlin where she became a writer and photographer in the fast-paced, artistic, and bohemian lifestyle that the city had to offer in the early 1930’s. She was notorious for drinking too much and using drugs, and she traveled all over Europe with friends and artists. However, this ended in 1933 with the Nazi takeover of Germany. Her family urged her to renounce friendships with such artists as Klaus Mann, an openly homosexual man and half Jewish writer. Annemarie refused, announcing she was a committed anti-fascist and helped other such artists with their works during this time. In 1935, on a return trip to then Persia, she married Claude Clarac, who was also homosexual, and so the marriage was one of convenience. They moved to Teheran together, but Annemaire continued to travel independently. For the next several years she visited Moscow, Austria, and Czechoslovakia, documenting the rise of Fascism; she traveled to America and documented the lives of the poor. In 1939 she attempted to combat her morphine addiction, as well as escape the violence rising up in Europe, by embarking on an overland trip with ethnologist Ella Maillart from Geneva to Afghanistan. They were in Kabul when World War II broke out.

Annemarie had a difficult time finding her footing after that. She fell ill in Afghanistan, which didn’t help her morphine addiction, and was rumored to be involved in numerous affairs. Finally in 1941 she began her career as an accredited journalist, traveling from Morocco to the Belgian Congo to Lisbon. In September of 1942, she fell from her bicycle and sustained a terrible head injury. Following a misdiagnosis, she eventually died on November 15, 1942; she was only 34 years old.

During her final illness, her mother stayed by her bed and turned away all of her friends from visiting her, including her husband Claude Clarac. After she died, Annemarie’s mother destroyed her letters and journals. Luckily, a friend saved Annemarie’s photographs and writings so that we may admire and learn from them today.

Albert Cashier was a transgendered pioneer from the nineteenth century, who’s best known for valiantly fighting for the North in the Civil War.

Albert Cashier

Albert was born in Clogherhead, Ireland in 1843, and became a stowaway to America at a young age. Working in shoe factories and as a farmhand, Albert presented as a boy in the years leading up to the Civil War, so as to live and work independently. He first enlisted in 1862 and was assigned to the 95th Illinois Infantry, where he fought for three battle-hard years until being honorably discharged in 1865. Upon returning to Illinois, he had all intentions of living his life as the quiet man his fellow soldiers knew him to be. He succeeded for the most part, working odd jobs here and there as a janitor, cemetery worker, and street lamplighter. Even when a few people in his life discovered his sex due to illness or injury, he was so beloved that they never disclosed it to anyone else.

Albert's tombstone

It wasn’t until he started showing signs of dementia in 1913, and was placed in a State Hospital, that his sex assigned at birth was discovered and he was forced to wear women’s clothing again - after 50 years of living life as his true self. Once the Veterans Pension Board discovered this, they threatened to cancel his pension because, in their minds, he had committed fraud. However, the men from the 95th regiment appealed to the board, arguing that Albert was the person they fought side by side with in the war, and that his payments should continue for life. When Albert died on October 10, 1915, the men from his regiment ensured he was buried in his uniform, and with full military honors. They also made sure his tombstone was inscribed "Albert D. J. Cashier, Co. G, 95 Ill. Inf."